When Voices from Ukraine Become Essential to Holos Ameryky Radio Broadcasts

|

Reporting for VOA in Newly Independent Ukraine

When Voices from Ukraine Become Essential to Holos Ameryky Radio Broadcasts |

![]()

By Adrian

Karmazyn

This year,

Over the course of that spring, I would file a report roughly every day that

would highlight some significant, unique or underreported aspect of Ukrainian

politics, foreign relations, economics, culture or social life. That approach

would, hopefully, help listeners better understand the situation in their own

country, within a global context and as seen from the perspective of an

American journalist. As any

reporter knows, covering a given topic can raise societal awareness about that

issue. Thanks to VOA’s longstanding

reputation as a respected and trustworthy news organization, when Holos

Ameryky spoke, people genuinely listened. Therefore, we tried to approach

our story selection very responsibly.

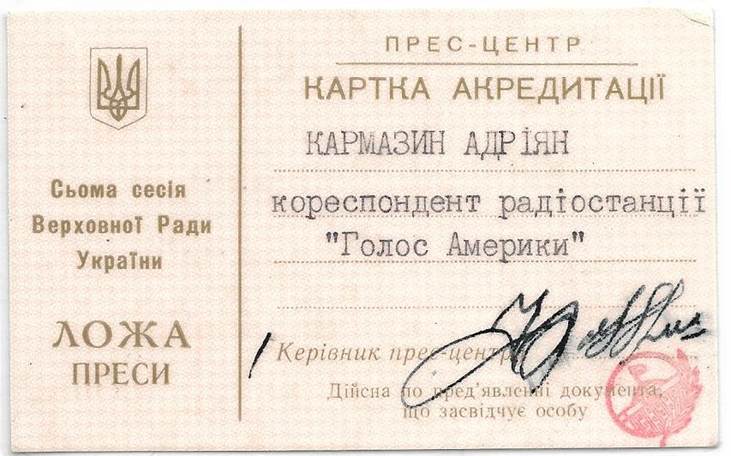

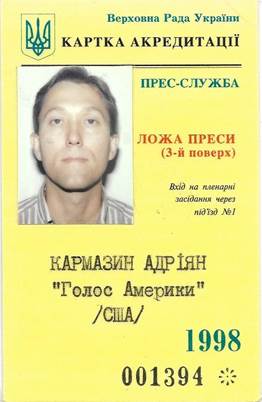

My parliamentary press pass.

So, what did I

report on in the spring of 1993? Below, based on the scripts I have in my

collection, I will share highlights from that eventful and extraordinary 90-day

assignment as a radio correspondent in

FOREIGN

RELATIONS

U.S. high-level engagement with Ukraine was quite vibrant during those months

as exemplified by the visits to Kyiv of Secretary of Defense Les Aspin,

Ambassador-at-Large and Special

Adviser to the Secretary of State on the New Independent States Strobe

Talbott, former National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski, and a high-level

Congressional Delegation which included Representatives Richard Gephardt, Bob

Michel, David Bonior, David Obey, Steny Hoyer and Newt Gingrich. House Majority

Leader Gephardt told reporters that “our purpose is, first, to say to the

Ukrainians that we think their country is very important to the region and the

world… And we wish them well in

their desire to have democracy and market reforms.”

He expressed hope that Ukraine would ratify the START Treaty and

emphasized that the delegation was making this visit in order to “be a

constructive partner with President Clinton” in putting together a new aid

program for this part of the world.

At the time, eliminating the nuclear weapons that

Congressional leaders Richard Gephardt (D) and Bob Michel (R).

In his opening remarks at a meeting at the Verkhovna Rada on April 5th,

Gephardt underscored

Coming on the

heels of the Congressional delegation meetings with Ukrainian leaders, Deputy

Foreign Minister Borys Tarasyuk characterized a Russian proposal to take

complete jurisdiction over the nuclear weapons on Ukrainian territory as a ploy

designed to place Russian forces on Ukrainian territory. “

Former U.S. National Security Advisor and one of

Brzezinski noted that

Among the other high-level visits to

It’s important to keep in mind that in March of 1993

In their

presentations, most Ukrainian ambassadors characterized foreign countries and

their peoples as having a positive attitude towards Ukraine and an interest in

developing cooperation at various levels.

The glaring exception was the statement of Ukraine’s Ambassador to

Russia, Volodymyr Kryzhanivsky, who said: “I must tell you candidly that, in

principle, we see that Russia is the only country with which Ukraine

continuously has conflicts. I would say

that no other Ukrainian ambassador works in a country with which there is

discord across the entire spectrum of issues.”

The dynamism of Ukraine’s new international engagement was particularly

apparent on April 15, 1993, when President Leonid Kravchuk was visiting Minsk,

Parliamentary Speaker Ivan Pliushch was in China and Prime Minister Leonid

Kuchma was traveling in the Middle East. And within days, Foreign Minister

Anatoliy Zlenko would be meeting with the Italian president in Rome and Pope

John Paul II in the Vatican. In a VOA interview, the foreign ministry press

spokesperson, Yuriy Sergeyev, explained the importance of these visits for

Ukraine’s trade, energy and other priorities.

(Years later Mr. Sergeyev would rise to the post of Ukraine’s Ambassador

to the United Nations).

NATIONAL

POLITICS

At the time, the dominant themes In Ukrainian national politics were the

difficult economic situation, hyperinflation and a steep decline in GDP, all

within the context of the inability of President Kravchuk, Prime Minister

Kuchma and parliament to reach consensus on a path forward.

The political gridlock and “old guard” dominance made it impossible to

adopt critically-needed economic reforms.

My reporting included the comments of various members of parliament

(MPs) representing various parties, including Mykhailo Horyn, Viacheslav

Chornovil, Les Taniuk, Valeriy Ivasiuk, Serhiy Soboliev, Oleksandr Barabash and

Vasyl Stepenko. Another important official at the time was the Vice Prime

Minister for Economic Reform, Viktor Pynzenyk, who warned of dire consequences

without more decisive support for reforms from the parliament.

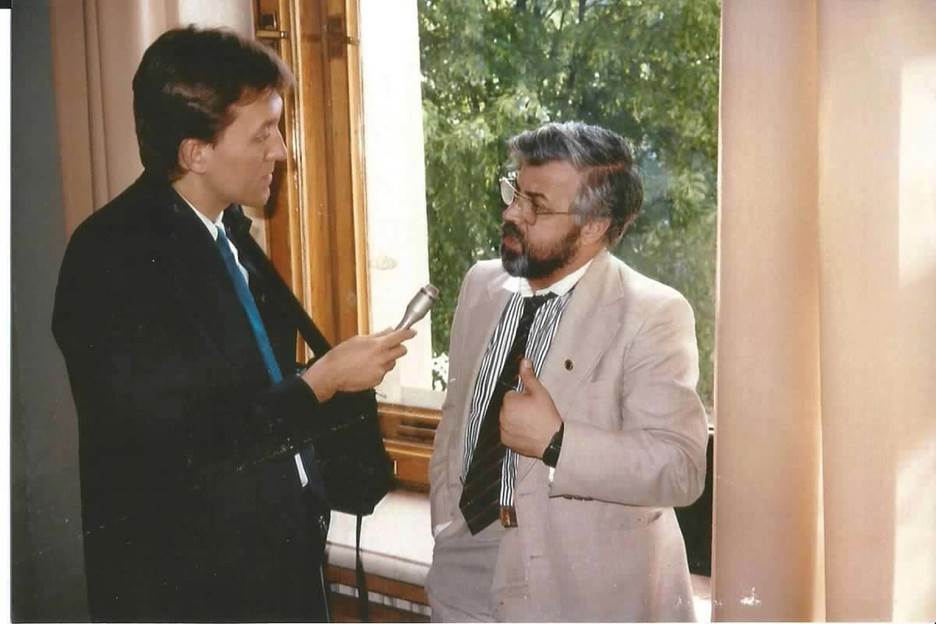

Interviewing MP Les Taniuk

at the Verkhovna Rada.

Another big national story was the 7th anniversary of the Chornobyl

catastrophe. Hanna Tsvetkova and Andriy Pleskonis of Greenpeace Ukraine talked

to me about their work in opposition to nuclear power in Ukraine and in keeping

people’s attention fixed on its dangers.

During a demonstration, Greenpeace unfurled a banner on Independence

Square (Maidan Nezalezhnosti) that read: “Chornobyl stopped time. Time

to stop Chornobyls.” The 1986

disaster and its aftermath had mobilized Ukrainian political activism and

contributed to the push for independence. Greenpeace

Ukraine reflected that spirit of participatory democracy.

MAYOR OF

KHARKIV

Besides

covering events and personalities in the Ukrainian capital, I felt it was

imperative to travel outside of Kyiv so that VOA could broaden the diversity of

opinion and viewpoints offered in our radio broadcasts, hopefully, leading to a

more enlightening listening experience for our audience.

At the time, I

considered my interview with Yevhen Kushnariov, the mayor of Kharkiv, to be

groundbreaking in terms of enhancing our Kyiv-centric programming with a

prominent voice from Ukraine’s industrial east.

Describing some of the challenges he faced, Kushnariov said: “Kharkiv is a very

big city, it’s the number two city in terms of population and number one in

terms of its industrial and scientific potential.

That is why Ukraine’s economic problems -- against the backdrop of the

economic crisis – have a very noticeable impact here in Kharkiv.

The main problem is for our economy to work normally.

Because if the very big enterprises in Kharkiv which are feeling huge

stress, first of all, due to problems with relations with Russia – if these

enterprises start cutting the number of workers and they end up on the

street—this will be a very big problem for the local government.”

In response, the city was providing assistance to factories to find new

partners and was starting the process of removing these enterprises from

government control, said the mayor.

Kharkiv also faced the problem of a huge budget deficit impacting the

city’s development.

Mayor Kushanariov was skeptical that Polish-style radical reforms could work in

Kharkiv, emphasizing that Poland had the help of two influential and

authoritative institutions -- the Solidarity movement and the Church – which

helped maintain social cohesion and peace: “These two forces were able to

restrain society from any unpredictable

events, which can arise when a large number of people experience a worsening of

their standard of living. This is

why measures that cause pain, at this point, are not possible in Ukraine. You

need to keep in mind the mentality of Ukrainians that live on this side of the

Dnipro in eastern Ukraine.”

Despite his skepticism regarding the privatization of large enterprises,

Kushnariov lamented the slow pace of small-scale privatizations, as he viewed

small businesses as a very promising sector for economic growth.

The parliament’s preference for long-term leases of communal property

rather than genuine privatization was tying the hands of local governments and

hurting the entrepreneurial spirit of small businesspersons, he said.

LVIV

PRIVATIZATION

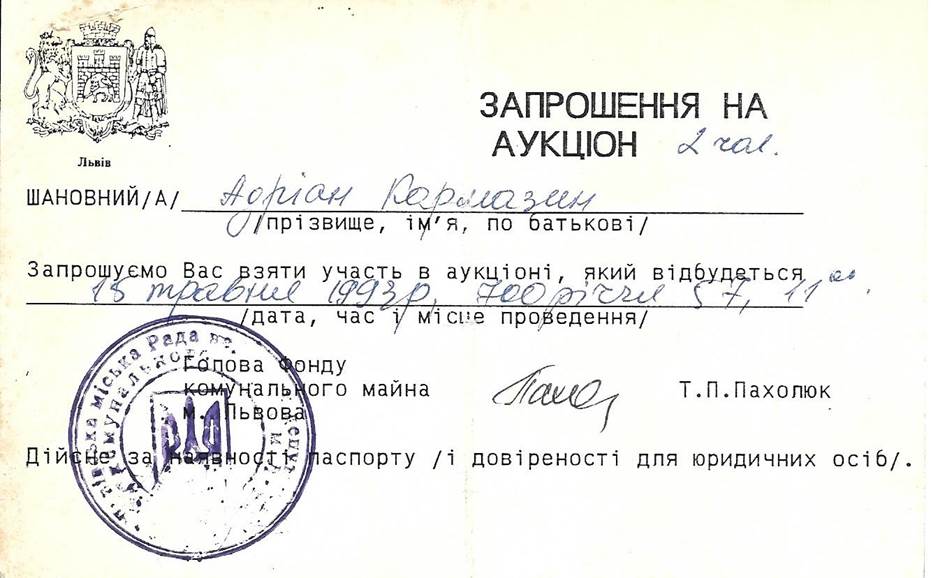

On May 15, 1993, Lviv held its second privatization auction, with disappointing

results. Only three of seven

communal sites placed on auction were sold -- two food establishments and a

laundry facility -- bringing the total number of privatizations in the city to

20. Although local authorities tried to be optimistic, two shop owners who

participated in the first privatization auction complained that hurdles to

success were disheartening. Mariya

Vlasiuk, a co-owner of the Yardan café, exuded entrepreneurial pride in

providing tasty food and drink to her customers but complained of excessive

amounts of paperwork in the process and the difficulty of covering the costs of

the purchase of the business with her very limited earnings. Meanwhile, Iryna

Yasnyska, owner of the Premier household goods shop, took pride in being a

pioneer in privatization efforts but complained that it’s difficult to fill her

shelves with goods since practically all enterprises are state-owned and won’t

sell to her. Plus, she viewed

government price controls that were instituted at the time as unfair and

contrary to market principles.

My invitation to a privatization auction in Lviv.

GENERATIONAL

SHIFT

As in many countries, generational differences in outlook and expectations

were quite apparent in Ukraine in 1993.

During my

visit to Kharkiv, I spoke with a group of students at the Karazin national

university, who shared their views about the situation in Ukraine and,

according to most, the need for rapidly jettisoning Soviet practices and

symbols.

The most patient among those I met was Dmytro Kolomayets, who said: “Really,

changes are happening although not very quickly, but perhaps they should not be

done too swiftly. It seems to me

that Mr. Kravchuk, our president, is a proponent of not changing things too

quickly so that they are not too painful for our people.

I think he is correct. We

don’t need to break everything… Perhaps we can restructure the old.

So, I believe that the changes are happening at the correct pace.”

However, Kolomayets’s classmates were not so tolerant of Ukraine’s Soviet

legacy. Mykhailo Hryzlov shared

his perspective: “My parents are ethnic Russians.

At first, I was against Ukrainian independence.

But now I accept this as a normal process.

If Ukrainians want to create their own [independent] state – I was born

in this city and grew up here -- I think it is a positive change if a people

achieve independence. But I would like to say that the main problem in the

independent states that were created after the collapse of the Soviet Union is

that they all have presidents that are former communists – Kravchuk, Yeltsin,

all of them. We achieved

independence from Moscow but not from the communists.”

Serhiy Ivannikov was critical of the pace of change in Ukraine: “Until we

undertake economic reforms, we will not be able to present ourselves as a truly

big European country. And we won’t

be able to conduct economic reforms until we have political reforms.”

This group of students had all participated in exchange program visits at

British or American universities and were keen on the prospects of Ukraine’s

integration with Europe and disappointed that foreigners know little about

Ukraine. Serhiy Novikov emphasized

that Ukrainians can’t blame foreigners for their ignorance about Ukraine: “We

should inform foreign countries and people about [Ukraine].

It has to be mutual.”

Separately, I met with the leader of the Ukrainian Student Union in Kharkiv,

Maksym Kovalyk. Although he had

not yet had the opportunity to study in a foreign country, he envisaged the

positive impact of having 1000 students from Kharkiv spend a month abroad: “I’d

like to see many more students take part in exchanges… at least for a month.

Perhaps this is a small amount of time for an internship, for study, for

the psychological impact of seeing [life abroad]… There will come a time when

we have a president born after the [Second World] War and we have to prepare

for that. We have to change the totalitarian psychology.

There are a lot of people who would want to… create in Ukraine a little

sanctuary for totalitarianism.

Perhaps under a different flag, but there are such people.

We shouldn’t hide this fact.

And exchanges of young people mean, first and foremost, a change in

psychology.”

As a graduate of agrarian studies, Maksym Kovalyk set a professional goal of

helping Ukraine’s farm sector: “I would like to devote a part of my life to the

agrarian sector. We still have

collective farms. It’s a tough

question as to whether we should disband them or reorganize them.

But we must pursue change, first of all, private ownership of land.

If there is an owner of an enterprise or of the land, then things will

happen, there will be work, and the owner will have responsibility.”

As Maksym

explained, the Ukrainian Student Union in Kharkiv numbered about 300 members

who were trying to “do something positive for Ukraine” and who have been

working on pushing the Komsomol and communist teachings out of university life.

It was established in 1989 and its first event was in support of the brutally

suppressed Tiananmen Square student pro-democracy protests in China. And

subsequently, Kharkiv students took part in the famous 1990 student hunger

strike in Kyiv, which eventually became known as the Revolution on Granite and

which culminated in the resignation of Vitaliy Masol, the Head of the Council

of Ministers of Ukraine.

Back in Kyiv,

I met with activists of the Union of Ukrainian Students who were also demanding

faster reforms.

For example, Valentyna Telychenko said: “Well, good, we supposedly got

independence and everywhere it is said that students are our future.

But in order to build the future it is very important to build up their

education now. Because the old communist system of education still exists and

it cannot properly prepare the cadres of the future.”

Vasyl Boychuk, the deputy head of the student organization who hails from

Ternopil, argued that after independence a new stage had arrived for student

activists: “Prior to independence it was one task, and after independence it is

a totally different job, because the way we worked does not satisfy us after

independence. That was a battle

for statehood, but now when we have a normal state, we need to build it, and we

are now thinking about how to build it so that everything falls into place more

quickly.“

Meanwhile, the head of the student information service, Volodymyr Nedilko, said

that independence means new challenges and demands for student youth,

particularly beyond material needs: “Besides your personal benefits, you should

see what you can do for your country.

You should be interested to see that your work is beneficial not only to

you but to those around you. And

that is why I try to do things that will support that cause.”

Vasyl Boychuk

added that the slow pace of reforms can be blamed on Ukraine’s historical lack

of statehood and on parliamentarians that instead of passing needed legislation

work only for their own narrow interests.

During the spring of 1993, Valentyna Telychenko, who eventually went on to

become a prominent human rights lawyer, was hoping to see more students enter

politics as they had already demonstrated that they could be a driving force

for change: “I think that students belong to that group which can most

significantly speed up democratic changes in Ukraine.

For example, let’s take the elections to the current parliament—to a

great extent they were driven by the student movement.

I took part in the election campaign and I know from personal experience

that among the democratic deputies [MPs] there was probably not a single one

who didn’t have two or three students on their staff. And this will even more

so be the case in the next elections.

I predict that a significant number of people seeking to become deputies

will be from among young professionals.

Their world view was formed when the totalitarian way of thinking had

become a joke and [so] they are immune to it.”

In retrospect,

reading the comments of students from that period nearly 30 years ago -- their

expressions of confidence, responsibility, freedom and idealism -- it seems

inevitable and only natural that they could and would be drivers of change.

When he was a 20-something in 1993, I wonder if Oleksandr Tkachenko, a

journalist with Reuters at the time, could have imagined that he would one day

become the Minister of Culture and Information Policy – a position that he

holds today. During our

interview nearly three decades ago, he radiated a feeling of freedom and

opportunity and he drew a sharp distinction between what he characterized as an

older more conformist generation and his peers.

Characterizing his peers as “a different generation” which came of age during

Gorbachev’s “restructuring,” he said: “These are people from 20 to 30 years

old. They have had the opportunity

to choose their path relatively freely.

And this is very good. They

are free people and they feel free and they will stand up for their principles.

This is a category of people that can’t be pushed aside.

They are a guarantee that we, here, will have changes for the better in

a democratic environment.”

Tkachenko very much wanted Ukraine to seize its opportunity: “Everything has to

be done to start genuine reforms, very quick reforms, so that Ukraine can show

the entire world that it is truly capable of doing something – especially in

comparison with [the political instability in] Russia.

And in contrast with that, win for itself the recognition in the world

community as a normal European country.”

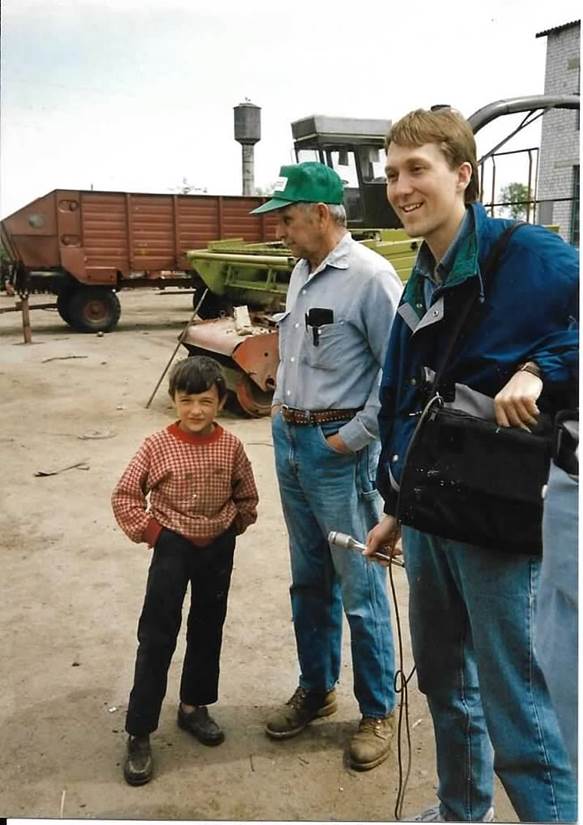

U.S. FARMERS

IN SLOBODYSHCHE

One of the most promising areas for Ukraine’s economy has been agriculture --

and back in 1993 the hope was that land privatization could be a key reform for

unleashing Ukraine’s agricultural potential.

That spring about 100 American farmers came to Ukraine as part of an

exchange program to share their know-how.

I caught up

with four retired, life-long U.S. farmers in the idyllic, bucolic village of

Slobodyshche in Zhytomyr oblast -- with nesting storks dotting the landscape,

just like those depicted in Ukrainian art and literature. The four farmers from

Iowa were engaged in a joint venture project, helping with the sowing of corn

at the Korolova collective farm. Their names (transcribed here from the

Cyrillic version in my 1993 reports to English) were -- Art Swers, Walt Napp,

Bob Buts, and Francis Kestner.

73-year-old Art Swers explained why these American farmers decided to take part

in the project: “We are farmers and in America farmers help one another.

We understood that Ukrainian farmers need help so we came with the goal

of helping.” He said he wishes the

Ukrainian farmers success in privatizing the land. “We know how much bounty

private farms have created in our country and so we hope to see that they will

have private farms here” in Ukraine, he said.

Francis Kestner, who along with his wife owns a 300-hectare farm in Iowa,

stated that he was happy to be here to lend a hand to his Ukrainian colleagues.

He was most impressed with the small, private garden plots that

Ukrainian farmers have: “I am most in awe of how much work the villagers of the

Zhytomyr region put into their [small] private plots.

If they can produce a good garden, they can have a good harvest out in

the field.”

For the local

Ukrainian farmers, it was their first-ever interaction with Americans.

They appreciated the idea of private land ownership but were concerned

about where they could get funding for the necessary farming equipment.

Although not much had yet changed in farming in the first year or so of

independence, one Ukrainian villager pointed out with satisfaction that “we

have plenty to eat.”

KHARKIV

ENTHUSIAST FOR AMERICAN KNOW-HOW

Back in Kharkiv, I had met with Anatoliy Yarokh, an energetic enthusiast for

spreading American know how. He

had traveled to the United States on an exchange visit and, subsequently, got a

job working for an exchange program which placed experienced businesspersons

from the U.S. at eastern Ukrainian enterprises and other entities.

International “communication is important, because Ukrainians in Kharkiv

and, generally, in Ukraine, are obtaining a lot of information, which was

unavailable earlier. They

communicate with real people, who share their experience and develop contacts,

which leads to commercial and business ties,” he said.

These exchanges, noted the native of Zaporizhia, impact people’s

psychology and their view of the Western world.

Furthermore, “many European countries, and especially America, set a

good example for us. Personally, I

would like to continue on my current path [of building contacts with the

world]… and to be useful to Ukraine.”

Anatoliy Yarokh (right) and VOA colleague Viacheslav Novikov in Kharkiv.

(1995)

HISTORY AND

HEROES IN POLTAVA AND KANIV

History, they say, is written from the point of view of the victors. A painful

example of this is the history of the Battle of Poltava, which plunged most of

Ukraine into stifling occupation by Russia for over 250 years. The victor, in

this case, being Peter the Great and Russia -- with Ukrainian hetman Ivan

Mazepa and his kozak forces, then allied with Sweden’s Charles XII,

suffering defeat. Henceforth,

Russian and Soviet historiography demonized the Ukrainian leader,

characterizing him as a traitor.

According to the deputy director of the Museum of the Battle of Poltava,

Oleksandr Yanovych, Soviet imperialist policy required that the museum present

hetman Mazepa in a negative interpretation and not as a fighter for Ukrainian

independence. But with the

dissolution of the USSR, it become possible, said Yanovych, to present Mazepa

and the 1709 battle truthfully, namely, that “the battle of Poltava was a

tragedy for the Ukrainian people.

Ukraine totally lost its independence. [It] was the first push towards the

Russification of Ukraine.”

From my visit to the museum in Poltava.

In our 1993 interview, Oleksandr Yanovych commented that Mazepa cannot be

considered a traitor to his people.

Quite the opposite. Through

his political and philanthropic activities, he did a lot to build up Ukrainian

statehood. And Yanovych explained

that the characterization of the 1654 Treaty of Pereyaslav as a “reunification”

of the Ukrainian and Russian peoples is false and only was promoted that way to

help quash Ukrainian independence.

Yanovych said that Ukraine regaining its independence less than two years ago

impacted the museum in a major way --- it brought stunning changes to the work

of the museum: “In the life of the Ukrainian people a new age has arrived –

Ukraine has become independent.

Now we have the opportunity not only to think about ourselves, but to openly

speak, to bring historical truth to the people without twisting facts, without

the politization of history.

Currently there is a big interest in our museum.”

Still, despite the new positive assessments of Mazepa’s historic role which

were taking place at the Poltava museum, as of the spring of 1993, Mazepa still

had not achieved the level of respect in his homeland of other Ukrainian

leaders or historic figures. In

the center of Kyiv there were streets named after Shevchenko, Khmelnytsky and

Hrushevsky but for some reason Mazepa had not been honored in the same way.

Liudmyla Shendryk, a staff scholar at the museum,

emphasized that Mazepa is deserving of more attention and respect from

his compatriots: “When talking about Mazepa, he should be honored at the level

of Bohdan Khmelnytsky, because as a political figure he is in no way inferior

[when comparing the two].

Historians have written quite a lot about Mazepa and if you study them all, you

can see that he was truly a person who fought for Ukrainian independence. And

he is a person who played a big role in Ukraine and he deserves to be honored

at a national level.”

In responding

to why Mazepa had not reached such a respected status in the view of most

Ukrainians or most then-current Ukrainian politicians, she said that they

probably do not know Ukrainian history very well and that history needs to be

studied.

With Ukrainian spring in full bloom, toward the latter part of my assignment I

traveled to Kaniv for a commemoration of Taras Shevchenko’s reburial there on

May 22, 1861. His initial internment took place in St. Petersburg but his final

resting place is a gravesite located on bluffs overlooking the Dnipro River.

My conversations with those that gathered there for the anniversary

confirmed that Shevchenko remained the most popular and revered Ukrainian. I

heard from his devotees about why they admire him so much.

Valentyna Shcherbyna of Kaniv exclaimed that she has deep reverence for Taras

Shevchenko because in his poetry he portrayed the suffering of the Ukrainian

nation, which is relevant today, more than 130 years after his death. She

respects Shevchenko “for his difficult life, because ours is no better,” and

added: “We have trust in him. We share our pain with him.

Today we are with him. But

we believe that if Shevchenko was resurrected from being forgotten, Ukraine

will also be resurrected.”

Meanwhile, Vasyl Tsybulko, also a local resident, said he respects Shevchenko

as one of those who helped establish Ukrainian statehood: “You can say that one

of the founders of our country is Shevchenko, Taras Hryhorovych.”

As for contemporary leaders, he gave credit to President Kravchuk for

being a figure that can unify the very different regions of Ukraine.

But Oles Cherednychenko, a music student at the kobzar school of Strytivtsi in

Kyiv region, lamented that newly independent Ukraine was short on heroes and

leaders of Shevchenko’s caliber: “We lack having people that will fight less

for fame and instead would fight for accomplishing things.“

By studying history, music and folklore, Oles felt he was making a

contribution to carrying on Shevchenko’s legacy.

NEW THOUGHT

LEADERS

As Ukraine marks the 30th anniversary of independence, it has no

shortage of insightful political analysts, commentators and journalists to help

shape the country’s narratives and media environment. Among them are such names

as Yaroslav Hrytsak, Oleksiy Haran, Mykola Riabchuk and Olha Herasymiuk.

As it turns out, I had interviewed them for our Voice of America

broadcasts in 1993, at a time when they were in the early stages of their

careers.

At his apartment along one of Lviv’s cobblestone streets, historian Yaroslav

Hrytsak explained the transformation going on in Ukrainian historiography: In

Soviet times, “the treatment of the historic process was to show that the

Ukrainian people came into existence simply

to unite with Russia, to go with Russia to the October Revolution and then to

live together in the Soviet Union.”

Now, said Hrytsak, Ukraine faces “a very complicated process of creating

a political nation” and historians are called to completely reexamine “What is

the meaning of Ukrainian history? …What is Ukraine? What is a Ukrainian?”

Oleksiy Haran, a young professor at the University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy and

author of Multiparty Ukraine helped explain to our audience the

political lay of the land in Ukraine.

After 70 years of one-party rule, he was quite enthusiastic about the

genuine democratic political competition between political groups, interests

and parties. Voters could choose from an array of democratically oriented

parties, including the Republican Party, The People’s Movement (Rukh), the

Congress of National-Democratic Forces, the Democratic Party of Ukraine, New

Ukraine and the Party of the Democratic Rebirth of Ukraine. But if they want

real power, they will need to cooperate more in the future to overcome

the dominance of the old-guard socialists in Parliament, Haran argued.

In an interview, literary critic Mykola Riabchuk talked about the crucial role

that civil society organizations play in pressuring the government to be

responsive to the demands of the country’s citizens.

Much of Ukraine has a weak tradition of civil society organizations –

especially under the severe constraints of Soviet rule -- but glasnost

brought a new energy to the sector and, interestingly, the Union of Writers of

Ukraine took on the role of an opposition organization, noted Riabchuk.

With the collapse of the USSR, independent political parties, media

outlets, civil society organizations, unions and businesses emerged.

Currently, Olha Herasymiuk is the chair of the National Council of Television

and Radio Broadcasting of Ukraine. Back in

1993, she was a journalist at Respublika newspaper. Just prior to our

interview she had participated in an East European forum titled A Free Press

Today and she shared this observation: “It turns out that we are all facing

the same situation – the euphoria from victory over the regime that existed has

passed. The euphoria from the

victory of democracy has passed.”

Herasymiuk explained that the old bureaucracy, corruption and the mafia have

made a comeback and journalists in the entire region are talking about how to

respond to this challenge, including through joint efforts.

Although there is freedom to write, there are immense financial

difficulties. Ms. Herasymiuk had

earlier participated in an exchange program where she was able to learn about

the U.S. media ecosystem.

Commenting on a year and a half of independent statehood she said: “To be truly

independent you need to have dignity” and “we are not filling it [independence]

with the necessary content.” It

was more of “a gift” than “something we fought for,” she mused.

With Olha Herasymiuk (left) and Irena Yarosevych.

During my visit to Lviv, I also interviewed Oleksandr Kryvenko, the dynamic

editor-in-chief of the Post-Postup newspaper.

The city was a major player in the independence movement, but after the

dissolution of the USSR it was suffering from a loss of a sense of mission and

from a bit of “brain drain,” with so many of its leading figures having moved

to Kyiv where all the action and decision making takes place.

So Kryvenko and I talked about what new role Lviv might find for itself.

One of his main complaints: There has not been enough emphasis from “democrats”

who came to power on promoting younger, market-oriented cadres.

Sadly, Oleksandr Kryvenko will not be present for the 30th

anniversary of independence, since he tragically died in a car crash in 2003.

CULTURE AND

FAITH

On the cultural scene, I had the opportunity to interview Ivan Malkovych, who

in 1992 founded the first Ukrainian-language private children's book publishing

business in independent Ukraine -- A-BA-BA-HA-LA-MA-HA.

He established the company because he felt there was a scarcity of good

Ukrainian language books for children.

Publishing books is a labor of love for the poet, who was responsible

for ordering difficult to find paper, loading trucks, recruiting illustrators,

editing the books, handling the accounting -- in a nutshell, overseeing every

step of the production and distribution of the books.

His aim was for the books to be read and shared in a family circle --

the place where he believes the rebirth of the Ukrainian language will take

root. “I want to publish original and nice books [and] … if I publish good

books, if the TV journalist makes good broadcasts, if mass media and

entertainment have positive Ukrainian figures -- children will be drawn” to the

Ukrainian language, he said.

In a clear

validation of Malkovych’s mission, by the time it marked its first anniversary,

his publishing company’s board book titled “Ukrainian Alphabet” [Ukrayinska

abetka] had sold over 70,000 copies -- an impressive feat for this

pioneering creative and entrepreneurial effort.

More recently, A-BA-BA-HA-LA-MA-HA gained fame for publishing the Harry

Potter series in Ukrainian.

Even with independence, things were not always going smoothly for the Ukrainian

cultural revival. Just weeks

before the planned May 29th opening of the Chervona Ruta

music festival in Donetsk, local authorities were still holding off with

approval of the event. With

regional competitions in full swing, I caught up with Eduard Drach -- an

awardee from the inaugural Chervona Ruta festival in 1989 -- at his concert in

Kyiv. He did not hide his dismay about the situation but, fortunately, the

problem was resolved and the festival successfully took place in Donetsk.

As an added treat that evening, music artists Mariya Burmaka and Vasyl

Zhdankin joined Drach on stage.

Highlighting newly won religious freedoms in Ukraine, I was able to capture on

tape the Easter-week sounds and sentiments of parishioners at the Ukrainian

Greek Catholic Sviato-Mykolayivska parish on Palm (Willow) Sunday and at

the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Tserkva sviatoho arkhstratyha Mykhayila

on Easter Sunday. The former was located in the Podil district of the capital,

while the latter stood on the grounds of the Ukrainian folklife museum in

Pyrohovo on the southern outskirts of Kyiv.

DIASPORA

During my interview with Oleh Skydan, an editor at Narodna hazeta and

deputy head of the secretariat of the Ukrainian World Coordinating Council

(UWCC), he talked about new opportunities to work with the diaspora since

independence: “Currently a lot of people from Canada and the United States are

coming to Ukraine, working here, they are teaching in educational institutions

or working as advisers or experts.

That is, they are trying to share their experience and, figuratively speaking,

laying their brick in the foundation of our statehood.”

On a recent trip to Britain, Skydan was so impressed with the

activities, institutions and dedication of the diaspora there that he decided

to join the UWCC. “That example of

service to Ukraine which we see in the Ukrainian diaspora of the West, it is

inspiring [and] inspires one to work here in Ukraine,” he said.

One of the Ukrainian-Americans who, along with her husband, came to work in

Ukraine, was Lida Kucher Shevchik from Detroit, Michigan.

She worked on U.S.-Ukraine academic exchanges. Being a witness to such

historic changes in the land of her parents was very special: “I have various

impressions. But my best

impressions are related to the opportunity I have to live and be here in

Ukraine, after having studied about Ukraine and studied the Ukrainian language

and culture [while growing up] in the USA.

It is very good to be here and in this difficult time to work and be of

assistance to a certain degree, in our own way.”

Interestingly, the first U.S. Ambassador to Ukraine was Ukrainian-American

Roman Popadiuk. I ended up covering his talk at the newly revived University of

Kyiv-Mohyla Academy. Thanks to the

Voice of America, highlights of his address could be heard by students

throughout Ukraine.

UKRAINIAN

VOICES

I made dozens of friends during my 1993 reporting assignment, and I’m grateful

for the kindness they showed in helping me figure out how to navigate the

nuances of life in newly independent Ukraine, especially from a journalistic

perspective. At one point we all

gathered together in my small apartment on Tarasivska Street in Kyiv for an

evening of good cheer in honor of my wife Sonia’s birthday.

It was a celebration like no other with Chervona Ruta music festival

laureate Mariya Burmaka singing beautiful songs from her repertoire -- the most

intimate concert experience imaginable. Somehow the legacy of Ukraine’s

decades-long isolation totally melted away that evening and it became

impossible to remember or imagine a Holos Ameryky radio broadcast

without the voices of people living in Ukraine.

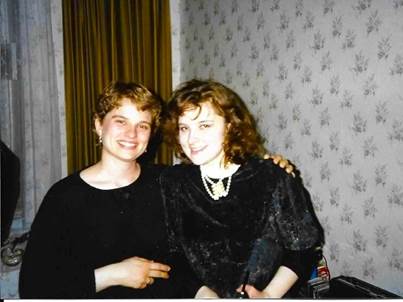

My wife, Sonia (left), with Mariya Burmaka, who sang for our gathering of

friends and colleagues.

RETURN

REPORTING TRIPS

In that first decade of Ukrainian independence, I had two additional extended

reporting assignments in Ukraine.

In 1995, I was a visiting reporter at Radio Ukraine International (RUI) as part

of an exchange program. Besides my

collaborations with the RUI team, my reports and interviews for VOA included: a

report on official and NGO responses to a French nuclear test, an interview

with Natalie Jaresko of the Western NIS Enterprise Fund, an interview with MP

Oleksandr Yemets, an interview with State Property Fund Chairman Yuriy

Yekhanurov, an interview with Tom Garrett of the International Republican

Institute (IRI), a report about the Ukrainian Publisher’s Forum in Lviv, a

profile of the Lviv Institute of Management, discussions with journalists from

UT-2 (Volodymyr Hutsul), Vikna TV (Mykola Kanishevsky), ICTV (Yuriy Kolisnyk)

and Vysokyy Zamok, an interview with Artur Bilous of the New Ukraine Party, a

report on the Ukrainian cultural revival in Kharkiv, my second interview with

Kharkiv Mayor Yevhen Kushnariov and a report on the Ukraine:

East-West Trade Exhibit in the city, a visit to two Ukrainian-language

schools in Kharkiv, an interview with U.S. Commercial Attache Andrew Bihun, and

report on a SABIT program participants’ reunion at America House.

In 1998, I had a two-month-long reporting assignment in Ukraine which included

an opportunity to sit in on focus group interviews in which listeners analyzed

and commented on our programming.

Although they were interested in American life, it was clear that they felt VOA

was not covering events in Ukraine comprehensively enough.

One participant said that over the past seven years “we’ve changed a lot, we

wish VOA would change with us.”

This group talked about the major improvements in Ukrainian media and asked

that VOA take a more serious interest in covering and analyzing events in

Ukraine. “Listening to VOA you’d think there is no news coming out of Ukraine,”

said one focus group participant. Another added: “I’d like VOA to talk more

about Europe and to analyze the situation in Ukraine.”

My reporting

on the Ukrainian economy, business, foreign investment and reforms in 1998

featured Oleksandra Kuzhel of the State Committee on Business Development,

Viktor Zubaniuk – a business magazine editor, Mark Kalenak of the U.S. Chamber

of Commerce and Petro Vanat of the Zaporizhia Union of Industrialists.

My reporting on the political situation featured MPs Borys Bezpaly and

Oleksandr Yemets of the generally pro-presidential People’s Democratic Party,

Vitaly Kononov of the Green Party, Oleksandr Slobodan of Rukh, Serhiy Sobolev

of the Reforms and Order Party, Petro Symonenko of the Communist Party, Oleh

Bilous of the Hromada Party and others.

One of the reports that I filed was a roundup of parliamentary reaction

to the president’s state-of-the nation speech.

Another highlight was a scene setter from Zaporizhia on the eve of a

visit of President Kuchma, featuring the governor of the province and a local

journalist. Also, I was fortunate

to interview former President Leonid Kravchuk on the seventh anniversary of the

referendum on Ukrainian independence.

At a hospital in Dnipropetrovsk.

I devoted a significant amount of my reporting in the fall of 1998 to

U.S.-Ukraine relations, including the visit of Stephen Sestanovich, the U.S.

Ambassador-at-Large for the NIS, who helped launch a new U.S.-Ukrainian-Polish

cooperation initiative. I

interviewed U.S. Ambassador Steven Pifer on a number of issues and also covered

his talk at Kyiv University. Other

reporting highlights included George Soros’ visit to Ukraine, an interview with

Taras Kuzio of the NATO information office in Kyiv on the Sea Breeze exercises

(which were strongly opposed by leftist parties in parliament) and several

USAID projects in Ukraine (including NGO development, medical and disaster

assistance, land privatization and legal support of independent media).

I also reported on the tourism industry and how government regulations have

been hurting its growth and on NGOs that provide social services to disabled

children. That assignment also

included my first ever trip to Dnipropetrovsk, today known simply as Dnipro.

It yielded a report on a hospital which received medical equipment from

the U.S.-based Children of Chornobyl Relief and Development Fund,

an interview with Anatoliy Bolebrukh – head of the history department at

Dnipropetrovsk State University, and an interview with Yevheniy Borodin – a

former U.S. exchange program participant who worked on youth issues in local

government.

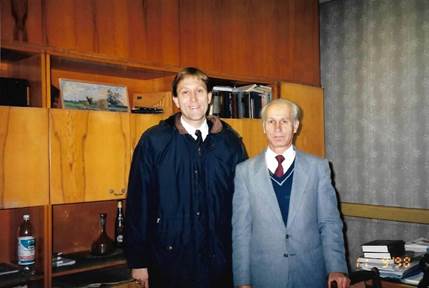

With Anatoliy Bolebrukh (right photo) and Yevheniy Borodin in Dnipropetrovsk.

In order to keep pace with all the important news coming out of Ukraine,

counter Russian and oligarch-controlled media, stay relevant, respond to

listener preferences and grow our audience, by the end of 1999 we hired four

local Ukrainian reporters in Kyiv to comprehensively cover the huge number of

consequential stories -- and the rotation of our American staff in Kyiv was

phased out. A decade of Ukrainian independence and ever-increasing U.S.

engagement with Ukraine meant that coverage of U.S.-Ukraine relations by our

Washington team and reporting from Ukraine would be a major pillar of our

Holos Ameryky radio programming mix. VOA had always been about “sharing

America’s story” but by the arrival of the new millennium that story included a

burgeoning and multi-faceted U.S.-Ukraine relationship.

-May 16, 2021

![]()